For the past two months, I have been part of a volunteering program in South Africa.

I decided to go back to the place where I did my internship and stayed in a reserve .

I contributed daily to the objectives of the program, which were:

- Monitoring all the animals once a day, or twice a day for the rhinos

- Monitoring the cheetah family

- Responding to any occurring emergency

- Fighting poaching in the reserve

- Collaborating with reserve management (guides and the anti-poaching unit)

- Learning about the wildlife living in the reserve

- Guiding volunteers

- Coordinating actions from the operations room

- Dealing with carcasses and placing them at camera trap locations

The schedule was very busy, and tasks were assigned based on urgencies, priorities, the to-do list, and staff availability.

One major difference from my initial internship was that I spent far more time in the bush and kept growing in the field, exactly what I was hoping to do.

When I arrived, I had the choice between sleeping in a tent with a wooden platform or staying in a room in the staff building next to where carcasses were handled. You can imagine that I chose the tent. It was a quiet place, and I loved hearing nature at night: lions, African barred owlets, fiery-necked nightjars, African scops owls, frogs… A myriad of sounds. I enjoyed it a lot.

I used to take a quick nap during lunchtime on the wooden platform and listen to the sounds at night. The first week was particularly tiring, being alert in the bush, even without doing intense physical activity, demanded a lot of energy. But after a week, I adapted, and my afternoon nap was no longer necessary.

I quickly fell into the rhythm of daily routines and adapted them depending on load-shedding and daylight.

If you don’t know what load-shedding is: it is a scheduled power cut, a measure used in South Africa to cope with energy shortages. Electricity for a region is switched off at specific times. For us, that meant no power from 5h to 7h and from 19h to 21h, the busiest hours of the day. Fortunately, the volunteer centre was powered by solar energy, so only energy-hungry appliances were affected: kettles, chargers, the water pump, etc.

I woke up every day at 4:45 to make sure I could get hot water for tea before load-shedding. I would leave camp around 6h for the morning tasks. Lunch was generally around 12h to 12h30 (unless tasks took longer). Office work started at 14h, and I headed out into the field again at 15h or 15h30, returning before dark around 18h, unless we were on a game drive. In the evening, I would boil water again to keep in a flask and hopefully shower before the electricity cut.

I loved the rhythm of the days: waking up early, making tea, entering animal data, driving out with the rising sun, searching for the animals during the day and falling asleep to the sounds of nature. It felt perfect. I loved being in sync with daylight and nature. It felt so natural. I never lingered at night and often went to bed early so I could be r

My three main tasks were either:

- Monitoring animals on my own

- Game driving with volunteers

- Performing operations room duties

Monitoring animals

Each morning we agreed on a plan and split the list of animals to find. The difficulty depended on the type of collar the animal wore.

Some animals wore a LoRa collar, which sent their location to our monitoring app (EarthRanger) at set intervals. When it worked properly, we received an update every one to six hours. That gave us a solid starting point, an important advantage compared to animals without location updates. Those animals only had a VHF collar, which emits a radio signal that we track with telemetry equipment.

For the latter, we would drive to their last known location, stop at high points along the way, and scan the area until we picked up a signal. Once we had one, we could triangulate the animal’s position and begin the actual search. Sometimes we spent the entire day checking every high point in the reserve without getting a single signal for a particular animal.

This happened often with the white rhinos. Finding them was far more complicated than what I experienced at the end of last year. Back then, the rhinos stayed together in a crash, but this time everything had changed. A new bull had been introduced into the reserve, disrupting the whole group structure. Some days the crash was together; other days, they were all completely separated.

One calf had no collar, so the only way to confirm his presence was to locate the mother and search for him nearby. Depending on the thickness of the bush, this was sometimes easy and other times required trying all possible angles, considering wind and sun direction.

One of the cows had also lost her collar. She was usually with another female, but not always. When we didn’t see her for several days, we started to get worried and made a plan to collar her again which made monitoring easier but disrupted the crash dynamics once more.

It was fascinating to witness how every human decision or action affected the animals’ lives and behaviour. The introduction of a new bull completely changed the group’s dynamics. The original, or “old bull,” as we called him, shifted his behaviour and began marking his territory far more frequently, as if redefining his boundaries now that he had competition. The cows moved between the two bulls’ territories, sometimes staying with one, sometimes with the other, sometimes alone, sometimes together.

The “new bull” established his territory after a period of adjustment and was known to be very insistent with the females, who generally didn’t stay with him for long. His arrival triggered significant behavioural changes within the crash. It was fascinating to observe and record all these dynamics.

Telemetry and Vehicle Use

A good way to start the day or the research was to take telemetry measurements from one of the highest points in the reserve: a koppie in the south that took about 20 minutes to climb on foot, a very steep walk. It was time-consuming, but it saved us a lot of effort later and gave us a rough idea of the animals’ locations in the southern part of the reserve. Any animal for which we couldn’t get a signal was assumed to be in the north. We reported all our findings to the ranger team so we could coordinate and make appropriate decisions.

I used different vehicles depending on the task: for short distances preferably the electric scooter that saves fuel, the motorbike or the ATV (quad) to cover all the game reserve and the game viewer for volunteers.

Maintaining these vehicles was part of the job.

For the motorbike and the quad, we had to fill the tank with petrol, check tyre pressure, check the chain tension, check oil levels, keep a tyre-fix canister ready, use a strong bag to carry carcasses, and report any unusual noises. The game viewer had a similar checklist.

After a while, the quad became my main vehicle. I fell off the motorbike seven times, and the managers decided to give me access to the quad for my own safety and also to keep the bike in decent condition. I was improving on the bike, but the smallest mistake meant ending up on the ground. Picking the bike back up and restarting it took at least five minutes each time. So, I planned routes to avoid the worst obstacles and got used to it, even if it meant taking longer detours or walking parts of the difficult sections. I was relieved when I could use the quad and started exploring the reserve much more without overthinking my route. This gave me more freedom.

What you quickly learn, at your own expense, is that the equipment doesn’t always work. Realising this in the beginning was a challenge. You use different instruments, some digital and some analog, and you need to know each animal’s frequency, fine-tune it, and re-enter it whenever it drops out. Having the wrong frequency, failing to spot a malfunction, or not ensuring the telemetry gear is fully charged can waste a huge amount of time.

And time is against you. You have to locate all the animals in a single day, and the rhinos even twice a day because of the high poaching risk they face. That means long hours, finding every animal, and doing it while trying to spare the equipment and resources as much as possible.

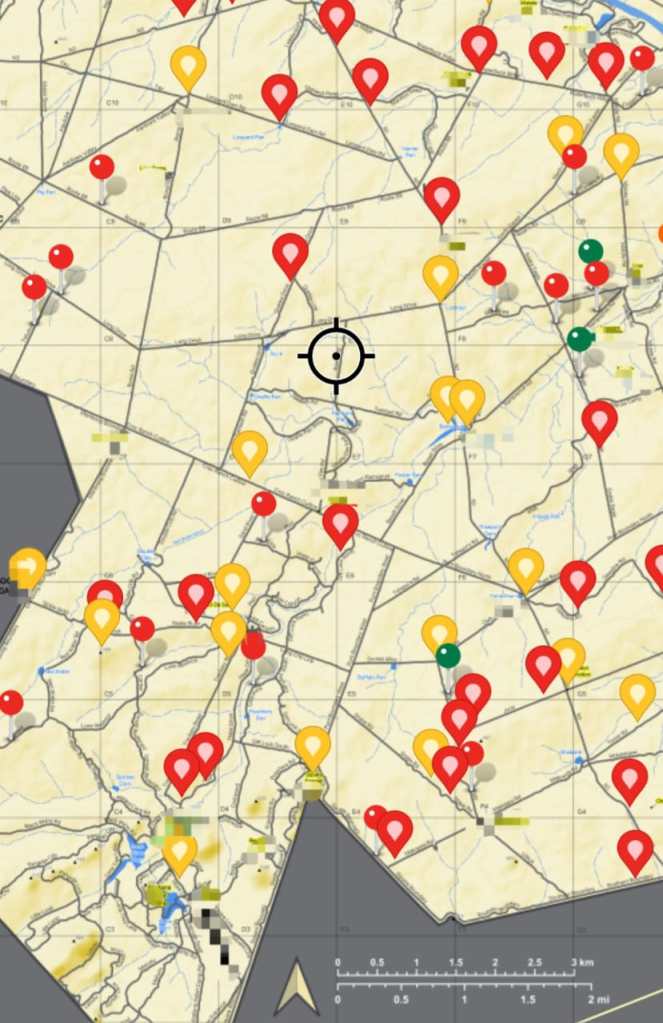

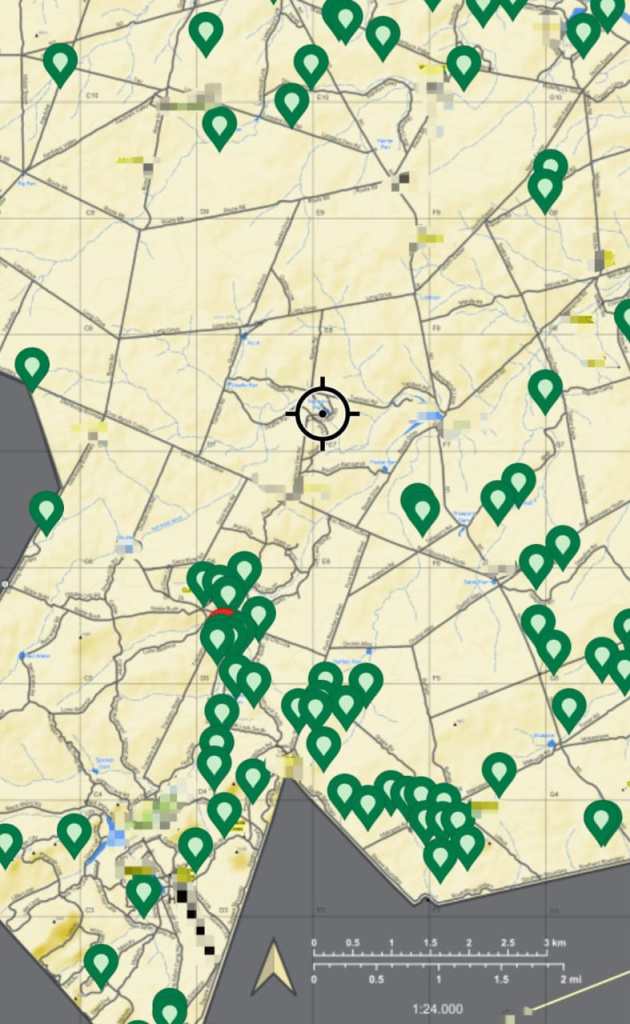

Part of my explorations was mapping high points for telemetry and understanding the reserve’s structure. These high points greatly accelerated searches. I created this updated map, with high points in red and the highest, broad-coverage points in yellow.

Still, some days were unsuccessful. I once spent the entire day trying to find a white rhino bull and only succeeded the next day. On the next picture, violet points were done in the morning and the red ones in the afternoon.

It was easier to find some animals than others. Some had recent satellite updates, which appeared on our EarthRanger map and showed us their latest locations. When the satellite updates didn’t work, the workload increased, as we had to search for all the animals from the telemetry high points.

Some animals were difficult to locate even when they were close. I tried to find the leopard many times; she was very skittish and a master of camouflage. I never saw her — I was only able to triangulate her position. At times I was very close, and she wouldn’t move away from me, but it was in vain. I might have been just 5 to 10 meters away, yet I couldn’t get any closer because of the dense bushes and safety considerations.

My daily pack included: water, sunscreen, telemetry, radio, handgun (or rifle with volunteers), first aid kit, raincoat, hat, and a phone for tracking and entering data in ER (EarthRanger). Occasionally I forgot something, but the telemetry and radio were non-negotiable. If I forgot the radio or the telemetry, I had to return immediately. It happened a few times in the beginning, but I improved.

Just another part of the learning curve.

Overall, I have done 166 observations on the field and recorded all of them. Below is an overview.

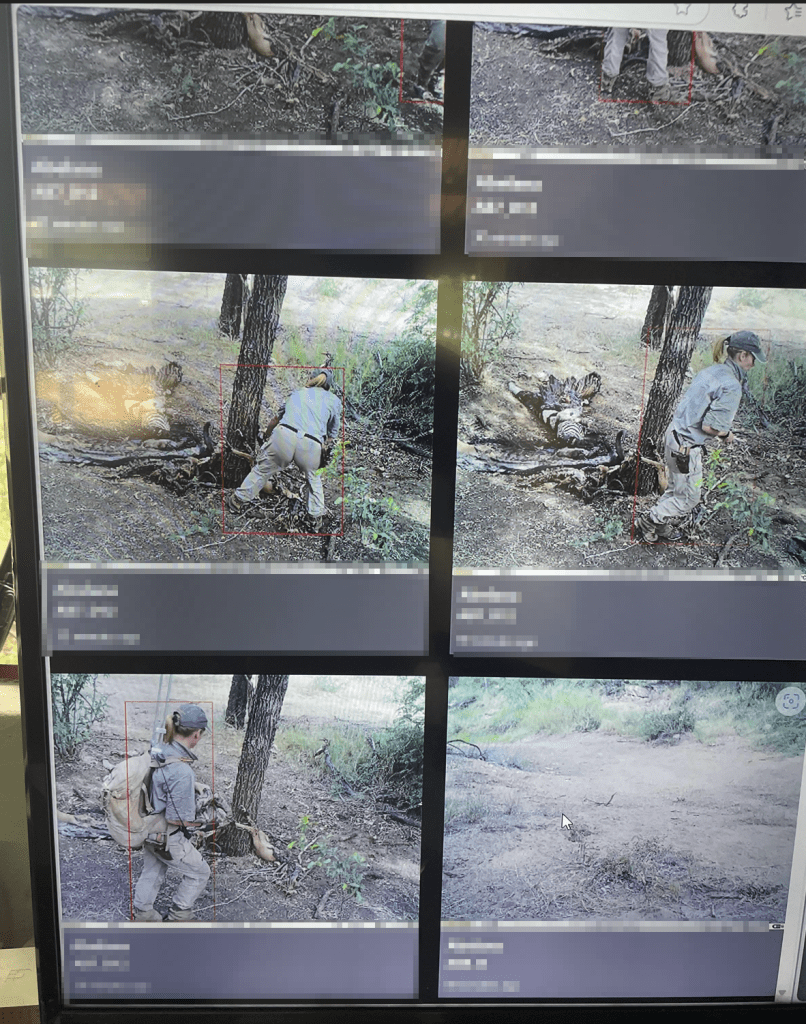

Carcasses and Camera Traps

The job involved handling carcasses, moving them to camera-trap locations, tying them securely using the tendons, and making a cut in the flesh so the wire could be fixed between the bone and the tendon. I was lucky that most of the carcasses I worked with were relatively fresh, usually from cheetah kills. You get used to it, it’s part of nature.

At the beginning of the year, I made a mistake when setting up a camera trap at a leopard kill. I tied the carcass around the neck instead of using tendons, and the leopard dragged it away, resulting in no photos. I learned from that and improved my setups afterward.

We used camera traps mainly to:

- learn more about wildlife territories, for instance for leopards

- support the hyena project, which aims to collar new hyenas and detect snare hotspots

Collaring new hyenas is necessary to identify areas where snares have been set. They are highly effective scavengers and quickly locate rotting flesh, so any cluster is worth investigating.

Part of the operations-room job is to identify wildlife by reviewing all the photos and videos captured by the camera traps. There is an ID kit that you can use and gradually develop. At first, it is extremely difficult — you don’t know how to proceed or which parts of the animal’s body to focus on. But with time, you start recognizing patterns, getting to know the animals and their territories. The more you work with the images, the easier it becomes. Once an individual is identified, you need to enter the data into the ER application, which feeds the database and helps us better understand the wildlife in the reserve.

Some camera traps are connected and solar-powered, and they notify you of any wildlife or human activity. Part of the operations-room role is to monitor this activity and inform the reserve staff or anti-poaching unit of any incidents. Ideally, when you set up a bait site, you should turn off the camera trap to avoid sending false alerts to the different units.

I forgot to do that at the beginning — as you can see.

When the bait site is no longer in use, we need to clean it up: remove the wires, take down the camera traps, and release the carcasses. This part can be very unpleasant to do. 🤢

Operations Room Duty

The operations room coordinates all field activities: tracking team movements in real time, following camera trap alerts, reporting suspicious activity, assigning tasks, and managing unforeseen events.

I spent a few days working in the operations room. I had to coordinate the team on the ground when we darted one of the cheetah cubs. It was stressful, you rely entirely on the information coming through the radio and have to give the rangers time to do their work. I hated the waiting part, not knowing in real time what was happening.

I did enjoy working on the ID kits and identifying hidden creatures through the camera traps. But I admit I prefer the thrill of working outdoors with the wildlife.

I was thrilled to assist in tense moments, such as retrieving the lions that had crossed into the neighboring reserve, de-collaring a hyena, and searching for an unknown lion that had entered the area, to protect our cheetahs.

Snare Sweeping

Part of the work involved finding snares. The areas we searched were defined by the operations room. Sometimes we also received information from the Eye in the Sky initiative: some vultures are tagged and monitored, and any vulture cluster is sent to us with precise coordinates, indicating a possible kill or snare site. Always something worth investigating.

At first, I didn’t have the right approach. I went directly to the cluster location and found nothing. But you need to sweep around the cluster and search the entire area. I learned this the hard way when my colleague rechecked one of my vulture clusters and found the snares and carcasses that had been hidden by poachers.

After that, I became much more thorough in my searches. I found some deactivated snares, probably removed by the poachers themselves, and one fresh site that contained a total of 64 snares. I used the Avenza application to track my steps so my searches were methodical.

Sometimes you search and find nothing. Sometimes you are less lucky, and animals have already been caught. And sometimes you find opportunistic predators feeding on an animal killed by a snare. This happened many times with lions, cheetahs, and hyenas. You immediately know when something is wrong and the kill is not natural, for example, when the head is hanging at an unnatural angle.

Here’s an example of snares I found when I was there; I already shared these in my previous article.

Sometimes you miss the obvious. See for yourself: I overlooked this one, which was actually found and reported by one of my colleagues, even though it should have been easy to spot. Let’s see if you can find it.

Guiding Volunteers

One of my duties, depending on the schedule, was to guide volunteers during wildlife monitoring. The target species and route were planned before the drive with the operations room. I loved walking the rhinos and the cheetahs. I avoided the lions when I was on my own, as I wasn’t comfortable walking them with volunteers without backup.

I monitored the solitary lioness alone once. I found her. She came toward me, growled, and kept approaching. I actually yelled at her and was ready to fire if she closed the distance, but she eventually lay down and let me leave. She was above me on the koppie, I faced her the entire time and I stood my ground. I was alone. I’ll admit I felt very small and was prepared for a real charge if she showed the signs. It wasn’t a pleasant encounter. Ideally, you stay unseen and observe the animal quietly from a concealed spot. But I had to see her. I needed a visual to make sure she was healthy, uninjured, and not caught in a snare.

Monitoring goes against many of the principles I was taught during my trail-guiding apprenticeship. You need a clear visual, and that sometimes implies getting closer, being seen, and being heard.

This lioness was skittish, and she became so after losing her sister. On her own, her behaviour changed; she started moving into denser, bushier areas. She failed to be accepted by the pride and was bullied several times. She’s occasionally joined by the males, and she even met the intruder male. We believe she spent quite a bit of time with him.

Somehow, she’s still surviving. She continues to roam freely and patrol the reserve. She follows consistent movement patterns and her own cycle. She’s a very capable hunter; she hunts successfully, sometimes in the riverbed. I once had to monitor one of her carcasses on an island in the riverbed. It was a massive warthog she had taken down by herself.

I really enjoyed wildlife monitoring with the volunteers. I did my best to show them the reserve the way I see and experience it. That meant stopping for almost any animal when we had the time, antelopes, giraffes, and even birds.

We shared some great adventures together. We once monitored a white rhino while a massive buffalo bull was roaming in the area, which I only realised when we got back to the game viewer. We had several memorable encounters with the white rhinos: the bull often let us approach quite closely and stayed completely relaxed, fully aware of us but showing no nervousness. The female with the calf, however, came much closer than expected, and I had to find a retreat for the volunteers to keep everyone safe. We also ran into the lion intruder while monitoring the cheetah family, a surprise for all of us. And we had a very close encounter with a herd of elephants that blocked the road and approached the vehicle. Some volunteers were not all feeling very confident, but we survived and had a great peaceful sighting.

Only good memories.

I also tried to teach them how to monitor the animals and use telemetry, explaining the reasons behind my decisions. I think they appreciated the transparency.

As I mentioned earlier, I avoided monitoring the solitary lioness with volunteers. But one day, I was assigned to check on her while all the other rangers were in different areas. We believed she might be outside the reserve as lions have been spotted in the communities the same morning.

So, I tried to locate her from the car, but as expected she was deep in the bush. I still remember the encounter I had on my own with her as if it happened yesterday.

I told the operations room that I wasn’t confident walking the lioness on my own with the volunteers, but they insisted given the circumstances. I had no choice but to be honest with the group. I told them I didn’t feel confident walking them to the lioness due to my limited experience. It wasn’t about me; it was about their safety. Saying it out loud felt uncomfortable, almost exposing. But they understood and appreciated the honesty. In the end, I offered to go alone. Two volunteers stepped forward and insisted on joining me to support me, which I deeply appreciated. It was a genuine act of generosity and courage.

We searched for the lioness, suspecting she had a kill. She found us first. She charged and growled. I remember standing my ground, facing the fear, and shouting, “Now you back off!!”

She did.

The relief was immediate and the mission accomplished: she was safe and in the reserve.

My adrenaline was through the roof. We returned safely to the car, and the volunteers who stayed behind had still heard the growl, which is impressive enough on its own.

I thanked the group wholeheartedly for their understanding. I explained what the encounter felt like: how facing such a magnificent animal strips life down to the essentials, the basics. I felt deeply grateful that day. Sharing that moment with them, receiving their support and trust, and talking it through afterward meant a lot.

I love this population of kind-hearted humans, people who care about nature, the planet, and endangered wildlife. I made genuine connections, some of which I hope will last. Writers, cyclists, mountain guides, tour guides, veterinarians, young people searching for direction, photographers… people from all over the world. A fascinating mix you get to know during game drives, over shared meals, or sitting around the fire on Sunday nights. Each had their own reason for being there. I enjoyed listening, even though I’m quite shy and a bit wild. I like one-on-one conversations, learning about people’s lives, plans, history, love stories, passions. There is always something to discover. Sometimes you even end up sharing your own story, maybe inspiring someone in the process.

In the end, it’s all about human connection and exchange—and it goes both ways.

Final Thoughts

So overall, I enjoyed this experience, and especially:

- Monitoring and spending time with the cheetah family; guiding guests and volunteers; sharing what I know about cheetahs and learning a bit more every day about their behaviour; seeing the spark in the guests’ eyes, which reminded me how lucky I was to witness those moments.

- Monitoring the rhinos; getting close to them; finding the right angle to approach them unseen and undetected; getting the visual I needed; searching for animals in general.

- Being on a cluster mission—whether for an animal or a vulture cluster—and finding snares. It was rewarding and gave me the feeling that the day genuinely mattered for the surrounding wildlife.

- Following nature’s rhythm: sleeping in my tent, hearing the sounds at night, and waking up before sunrise.

- Meeting amazing people and making new friends.

- Getting better at my job every day—telemetry, equipment, monitoring, guiding techniques—and improving by doing.

- Getting to know the area by heart, finding my way easily, and learning the animals’ habits and preferences.

- Feeling the wind on my skin while driving across the reserve, enjoying the perfect sunny weather despite the drought.

- Crossing the bridge on a motorbike or scooter when the water flowed over it.

There were tough moments and things I disliked. It wasn’t always easy, even if I was living a dream:

- The tick bites. You have no idea how many I got, especially the “pepper ticks,” the early-stage ticks that get into everything, even when you wear long pants. I was literally covered in them. Walking through long grass or brushing against a dense patch could mean hundreds of them at once, and you had to brush them off immediately, always leaving some behind anyway.

- The lack of resources, the equipment failures, and everything that went wrong when the schedule was already tight. It added pressure, but those failures also taught me a lot and pushed me to improve.

- The really thorny bushes, especially knob thorns. You know them, you try to avoid them at all costs, but there’s always that one tree or bush you didn’t see that ends up hooking you.

- I don’t think I integrated well into the team. I often disagreed with decisions and how they were enforced, and I didn’t feel listened to when I spoke up. I felt alone many times, but the wild landscapes and the wildlife made up for it and kept me going.

- Falling from the motorbike, multiple times.

In the end, I am deeply grateful for this experience. I lived something extraordinary, especially with the cheetahs.

However, I have decided not to return in the short term. I don’t think it is the best use of my skills. I want to apply my management experience, digital and computing skills, analytical abilities, creativity, and project management expertise to causes that address root problems, not just symptoms. It felt we are mostly acting on consequences rather than addressing the deeper issues, especially those involving surrounding communities and young generations.

I want to contribute on a larger scale: something built to last, something meaningful, a virtuous circle that brings communities and wildlife together. As much as I enjoyed observing the wildlife and understanding them a bit more every day, I believe there are other projects where my skills and perspectives would be more useful.

I’m looking forward to the next steps, which will take me to Tanzania, Zimbabwe, and Papua New Guinea in the coming months. Maybe I’ll find something worth fighting for.

Thank you for reading until the end. Stay tuned, I will keep sharing my adventures

Leave a comment