As usual I write on the move and on my way to Windhoek and back to Europe.

I was supposed to stay in Namibia for the next two weeks, but my student visa issue decided otherwise. I am still trying relentlessly to get it sorted out before my flight in South Africa.

About my visa

Weirdly enough, the South African embassy contacted me during my trip in Namibia, two months after my appeal request, despite the reminder emails I had been sending them. They asked me to fill in an appeal request form and resend the PDF documents I had already sent them two months ago. Clearly, they hadn’t processed my request at all during that time. It felt like I was back to square one. I had to fill in the PDF form in the middle of the night, in the desert, during patrol week, and I had to write it out by hand because I couldn’t type on my mobile. It took me ages.

I was really desperate and frustrated; you have no idea. Despite all the effort I put into it, the process didn’t go according to plan. Apparently, they had a lot of problems with their system, which they used as their justification. I hate not being in control; there was nothing more I could have done. I even used my network, but in vain. I just have to let go.

This time, I stated my constraints and timeline in the most diplomatic way, despite my anger, asking them to treat this request with the utmost urgency. At least, I received an acknowledgement directly. It’s a never-ending story that started in March and is still not resolved. I hope for the best, but I am not sure of anything now. Sometimes, despite all the effort and energy you put into something, it doesn’t always go the way you want. It must be for a good reason, though I don’t understand it at the moment.

That’s a side detail to help you understand my journey and some of its incoherence. Why fly back to Europe when you can easily go from Namibia to South Africa? That was my original plan. As usual, I will make the best of it and enjoy the opportunity to see friends and family for the next 15 days while addressing the issue.

My experience with the desert-dwelling elephants

Now, let’s talk about the elephant in the room: my experience in Namibia with EHRA and the desert-dwelling elephants.

I think I am probably going to repeat myself, but I am really grateful to have had the chance to live this experience. Doubts persist about the future and how I am going to make my way through. My journey has brought me far since November last year and the waves of doubt that were submerging me then. I feel I am on the right track. All my senses were alert, my cells were vibrating. I felt alive. It may seem obvious or simple, but that’s just how I experienced it.

Being in the wild for a month, having a shower once a week despite the hard work, seeing beautiful desert landscapes on the horizon, hardly encountering any human beings, enjoying the silence, paying attention to the surrounding sounds, the cracks of bonfires, the gentle heat of the sun in this season, learning about nature: animal names and their behaviors, trees and their properties, meeting great people and having interesting conversations, learning about human-elephant conflicts, witnessing them and their complexity.

My brain and mind were at ease. And last but not least, having the great opportunity to observe wild, desert-adapted elephants in their environment, assessing how majestic and impressive they are. I was thrilled during my first safari; I saw elephants up close. This felt different, a level up, I would say. You get to know the herds, their names, their behaviors, their background, and history. How peaceful they are despite the different conflicts with humans. You start to recognize them. You slowly get attached to them.

The tracking moments are priceless. You find a bull, the herd, following their tracks, understanding how to read them: how fresh are the tracks? Is there any evidence of their passage around here, like leaves or broken trees? Which direction are they heading? How many are there? Any other clues like poop and pee, and how fresh are those clues? A genuine investigation to get the chance to observe them, to assess their health, to count them, and register their movements.

You start to understand what kind of organization EHRA is from the ground, from within. This association has existed for more than 20 years now. It began with an unexpected encounter between a great elephant bull named Voortrekker and an open-minded human being, marking the beginning of their friendship. At that time, in that region, the elephants were wilder than they are today, and a long journey had just begun.

Now, they have developed several projects over time:

- The volunteering program with a two-week cycle aims to build walls and help reduce conflicts between humans and elephants during build weeks, along with wildlife sight-seeing, data registration, and assessments of HEC (human-elephant conflicts). I will come back to this.

- The peace project aims to educate the population on how to deal with elephants, bringing awareness through training the elders.

- The seed project targets the next generation.

- Elephants’ identification and localization aim to inform the population and commercial farms when herds/bulls are entering their areas.

- Installation of electric fences and solar panels to protect gardens and crops, reduce costs, and reliance on fossil fuels and expensive energy sources for the local community when providing water to the communities and elephants.

- Analyzing elephant behavior and working with commercial farms to find common solutions to avoid conflicts and investment losses.

The 2023 annual conservation report is worth reading to understand the missions of this organization.

Funding is primarily private, with the main sources being volunteers and donations, which represent 60% of their total budget.

Before going forward, presenting the context might help. The desert-dwelling elephants are wild animals. They are not part of private game reserves or national parks with fences. As such, they can wander wherever they want in the area to feed themselves and survive, including heading to villages.

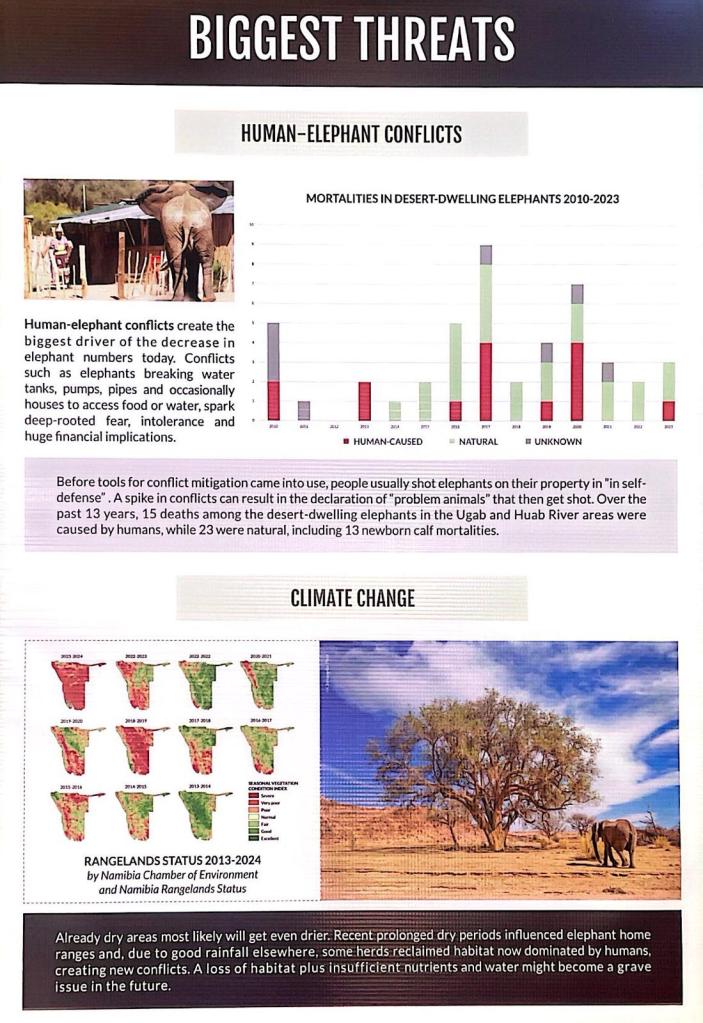

The elephants are endangered due to several factors:

- High mortality due to drought and climate change.

- Reduction of their habitat, increasing human-elephant conflicts. When elephants are considered problem elephants (dangerous behaviors towards humans, repeated destruction of human facilities and commercial farms), the government may provide licenses to kill, or elephants might be shot under specific circumstances.

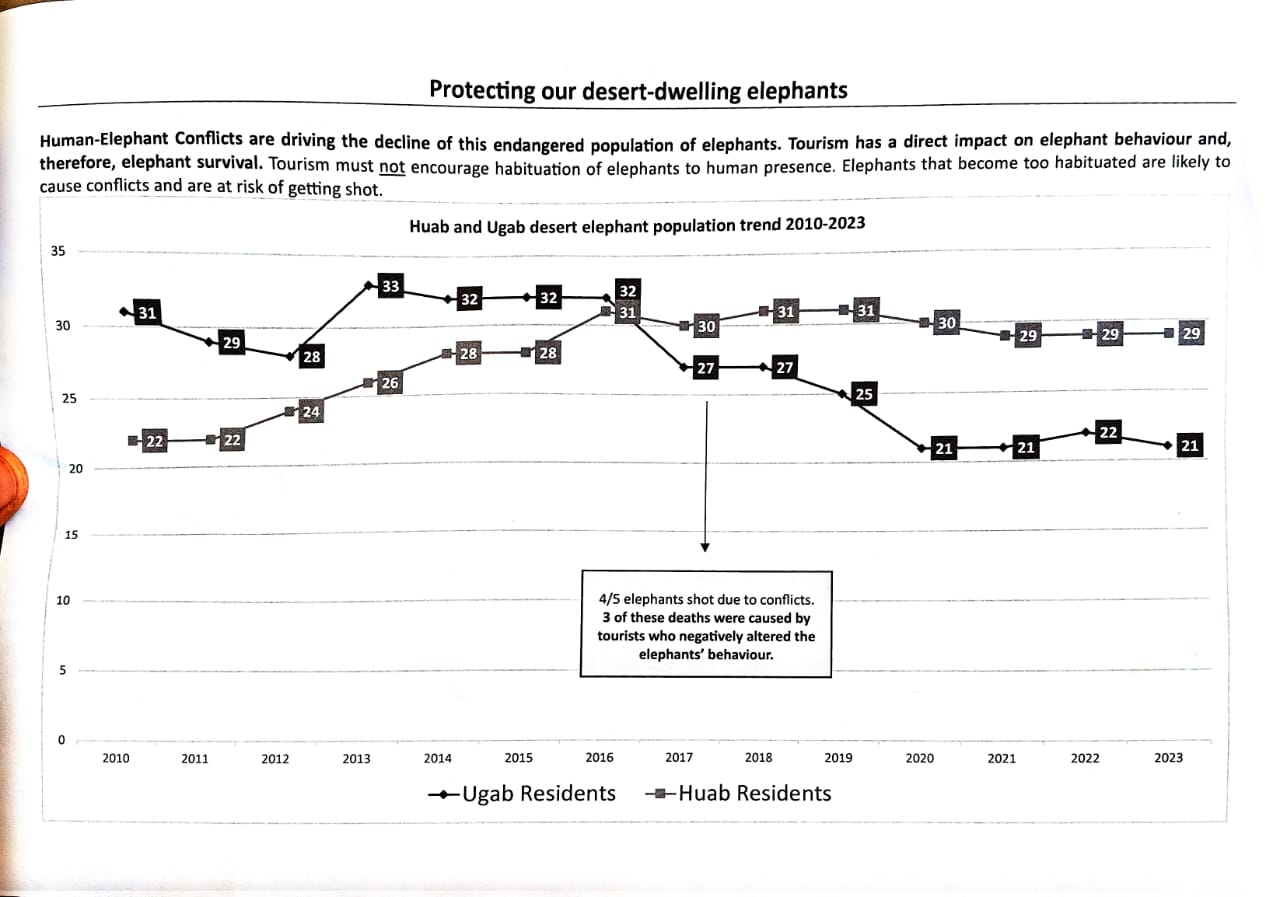

- Proximity to tourists and guides who may not respect the rules (staying in the car, maintaining a 70m distance from the elephants, feeding the elephants), inducing the wrong behaviors in those elephants and endangering them at the same time.

- The expected increase in tourism when the road between Swakopmund and Uis is completed.

The overall and remaining population of desert elephants in Namibia and Mali is decreasing progressively as a result of human activities.

Despite all the efforts, projects, and rules set in place, the elephant population with the greatest interactions with humans is decreasing.

Here is an overview of the rules and impacts on the population. The Ugab River herd is the most exposed to humans. I guess the figures speak for themselves.

The task is tremendous but worth the effort, and I believe in the actions of EHRA. The idea is to fight against harmful human behaviors by increasing awareness and creating infrastructure that enables coexistence:

- Ensuring the local population understands how to deal with elephants: respecting community infrastructure that attracts elephants away from villages, hiding hosepipes by digging and burying them underground, and protecting their households and crops.

- Ensuring the community understands the importance of elephants in the environmental cycle and in terms of revenue generation.

- Creating infrastructure to allow elephants to drink and feed away from human settlements.

This sets the context.

Now let’s get to the volunteering activities and how I experienced them.

First of all, the arrival in Namibia. I was expecting a busy, happy mess based on my former experiences in Africa, particularly in the North. Not at all. Namibia looks like a European country—clean, with well-maintained roads, and wealthy. Apart from driving on the left side of the road and some different road signs, it’s really similar to Europe. Let’s not be blind, townships exist; I have been told about them and saw one when we passed by Swakopmund. There is a huge gap between the wealthiest and the poorest.

MY FIRST 2-WEEK CYCLE

We were a group of 7 volunteers, which is low for the season (groups can reach a maximum of 14 people), accompanied by 3 to 4 guides depending on the week. Different countries: Germany, Switzerland, England, and France. Different ages, from 19 to 70 years old, and different backgrounds (retired specialized technician, paralegal, vet, students in gap year). It was funny to see that among all of us, 3 had resigned from their positions and were willing to contribute differently or travel.

Sunday, June 2nd

Arrival in Swakopmund and first encounter with the group and the guides during an evening briefing with a presentation of EHRA activities, the two-week program, a round table introduction, a review of necessary items to buy if we forgot anything before departure, followed by a convivial dinner to get to know each other. We also met former members of the previous cycle (some are repeat volunteers). We received a lot of information from previous volunteers who did not hesitate to share their experiences and tips. A warm welcome. It looked very promising to me.

Monday, June 3rd

Morning shopping: lunch, a blanket, snacks, electrolytes, and cough and sore throat medication for me.

We headed to EHRA base camp after a 5-hour drive, discovering desertic and amazing landscapes. On arrival at base camp, we started to organize the group into daily rotating duty teams (responsible for cooking and dishwashing) and received a safety briefing (including but not limited to setting rules for alcohol consumption, forbidding illegal drugs, awareness of the 3 S’s: scorpions, spiders, and snakes, the necessity of a head torch at night, behavior towards elephants, and the necessity to inform the staff of our movements).

EHRA base camp is amazing, suited to its environment, and sustainable, consisting of a kitchen, a workshop, an educational center, a tree platform, storage rooms, long-drop toilets, showers, a fireplace, and sorting garbage bins. Everything uses mostly local materials, and it is located next to the river bed where elephants sometimes pass by. It was our first night under the stars using our swags or bedrolls and sleeping bags. The night sky was amazing with no light pollution, the ability to see the Milky Way and learn the new constellations. It was almost a new moon, and the sky was dark.

Tuesday, June 4th

Wake up at 6 to start breakfast, with departure planned at 8 to the build site after a 90-minute drive and what they call nice African massages. We packed everything in the minibus, trailers, and 4×4: building tools, camp elements, food, bedrolls, kitchen utensils, and our belongings.

We arrived at the wall. Setting the scene for the week to come. The last part, between 1m and 2m, needed to be finished by Saturday morning. It was feasible even with a small group of volunteers, hard to believe in my opinion. The task looked tremendous.

We set up our build camp for the week: the main tent, tarpaulins, firepit, biopit, and long-drop toilet. Everything is well thought out and organized. A real “leave no trace” camp, limiting our impact on the environment.

First lunch and off we went. The tasks were divided into the following activities:

- Rock runs: using the 4×4 and trailer, we collected big and flat rocks from the environment. There is a technique to avoid hidden insects and danger underneath; you have to flip the rock in the opposite direction of where you stand.

- Sand runs: using shovels, we collected coarse-grained sand and brought it to the build site.

- Mixing cement in the wheelbarrows with the help of shovels.

- Building the wall, which consists of applying cement while performing a rock Tetris.

The wall consists of an inner layer, an outer layer, filled with rocks and cement, separated by at least 3-4 meters from the point to protect, with an approximate height of 2m. EHRA provides the walls and finances them to protect boreholes, solar panels, and water tanks in exchange for a counterpart from the owner. In this case, the owner provided the borehole and water to the community; in other cases, they may be asked to create a water dam for the elephants.

From Tuesday to Saturday, June 8th

The overall timing of our daily routine was:

- 6:00: Duty team starts to light the fire and prepare drinks.

- 6:30: Wake-up call with hot drinks.

- 8:00: Work starts after breakfast and brushing our teeth.

- 8:00-10:00: Hard work.

- 10:00-10:30: Tea break.

- 10:30-12:00: Hard work.

- 12:00-14:00: Lunch and resting time.

- 14:00/14:30-17:00: Hard work under the blazing sun.

- 18:30: Sunset.

- Dinner and evening usually ended around 21:00, sometimes earlier.

- Night under the stars, under the tarp, in a tent, depending on individual preferences (I chose the night under the stars each time regardless of the cold, wind, and wetness; I couldn’t resist it and I loved it).

My Impressions

First of all, the group, in its large sense, including guides and volunteers. It was a very diverse group of all ages, nationalities, cultures, and backgrounds. If you think about it, how could such a group work together so well? I guess we had some things in common: the willingness to share, to participate to the best of our abilities, our curiosity, mutual respect, patience, open-mindedness, a genuine interest in each other, and a common goal set by EHRA. Truly impressive to live and experience. I am grateful to everyone who contributed to such great teamwork and atmosphere.

The Physical Work

I knew it would be a challenge for me. How would I cope with the physical work in the deep heat? I have been working at a desk all my adult life; I haven’t done anything with my own two hands before this experience. I’m more of a mental person than a manual one. What about my knowledge? Fun fact: nothing I have done so far has been related to this type of work. And the practical aspects: Will I freeze to death at night? (Manner of speaking) What about mosquito bites and all the insects? Will I be well integrated into the group? Etc. I had all those doubts before meeting the group and being in Namibia. I know I am persistent and could get there eventually, but still.

First of all: no mosquitos but a scorpion under my mattress. The night after was difficult; I was thinking of that scorpion all the time. I had to accept it is just a lottery and live with it, which I did (but also, it hasn’t come back, which helped a lot).

During the Building Time

I worked hard but also tried to manage myself, knowing my limits while contributing to the best of my abilities. Everyone accepted this and respected each other. The rhythm set by the guides was perfect and clearly helped a lot. We rotated tasks to manage efforts and ensure we didn’t get bored. The food was delicious and greatly contributed to our morale. I even think I gained some weight during build week—imagine that!

I was truly amazed at how we managed to finish the wall on time and how quickly it went, thanks to teamwork. As one of the guides said, “We are stronger together.” It’s obvious, but experiencing it firsthand is priceless. Considering the size of our group, I really didn’t think we would finish the wall by Saturday morning, but we did it as a team, with everyone, including the guides, contributing to the success. Having a clear objective certainly helped.

We also had the help of a local shepherd who joined us for the entire week. It made our actions more tangible, and we could see the results, realizing how important our work was. We saw the inhabitants coming and using the water. Some of us even heard elephants passing nearby during the night. This added texture and depth to what we were doing, and we could clearly see its impact directly on-site. What a privilege to contribute directly to a goal larger than ourselves, witness it, and be part of it.

We had great weather—not too hot but challenging enough, especially in the afternoons. I’m grateful for that. We drank a lot of water, took deep breaths, smiled, and avoided dehydration.

I cherished all the good moments: the shared discussions, the “million stars hotel,” the bonfire in the morning prepared by our favorite fireman, the knowledge sharing, everyone’s availability, the beauty of the landscapes, the positive mindset of everyone, the laughter, the teasing and jokes, the golden silence, the quality of the equipment and camps, the complete nights… and many more.

I really enjoyed it despite the difficulty and the challenge. It was rewarding from my perspective: the physical aspect of enduring the heat and seeing the results directly kept me motivated at all times.

This work is quite different from the humanitarian project I did in Togo in 2020, where we funded a school. We hardly contributed physically, and the locals were in charge of the labor. This time, I was part of the building work directly. It felt right, as if I healed some parts of my past too.

Anyway, we finished the wall and were absolutely thrilled with the results!

After build week, we returned to EHRA base camp. We had a day off on Sunday in Uis nearby. We had lunch together and enjoyed some time with Wi-Fi, electricity, and connecting with family to let them know I was still alive and having a great time.

PATROL WEEK

From Monday, June 10th to Thursday, June 13th

We were on patrol week. We had to pack light since all our stuff needed to fit into the 4×4 we were sharing. The rhythm was as follows:

- Between 6 and 8, breakfast and camp packing.

- Lunch at 12 until 14 or 14:30, depending on the weather.

- Establish camp at 17, cook, and bedtime, generally around 21.

We changed location every day.

During our week, our mission was to check on the Frenzy herd, 2 hours east of base camp. This herd is wilder than the Ugab River elephants, and it was uncertain if we would see them. However, according to our local guide, Nikky, they were close to the road, and we had a chance to spot a calf. One of the elephant cows is collared, so we could confirm their exact location with the office software.

Soon after our departure, we encountered a human-elephant conflict as one of the elephants had broken some water pipes. They were not buried and were unfortunately just lying on the ground.

On the way, we passed by a bull supposedly 1 km away from the road, named Porthos. We had to check on him as he might have broken one of his tusks. This bull didn’t want to be found and kept fleeing from us. It took us two hours to get a glimpse of him by driving off-road, climbing koppies, and searching with binoculars. Eventually, we saw his back as he ran away, and we lost his track without confirming anything about the tusk.

After lunch, we arrived near the Frenzy herd, picked up our local guide, and went to check on them. Driving off-road in the bush was harder here due to thicker vegetation. We couldn’t get close to the herd despite our attempts, so we camped near a water point, hoping they would come to drink at night, allowing us to see them in the morning.

We did manage to get closer to them the next morning, approaching on foot. We followed the guide and tracker, with a small delegation going first to try and get pictures of the calf. The wind and light conditions were in our favor, but I was not reassured. We didn’t know how the herd would react—whether they would charge or flee. I trusted the staff, though, as they were experienced. It was impressive how they could spot the elephants long before us. Moments like these made me realize how small and vulnerable we are, and how noisy we can be even when trying to be silent. Despite our efforts, we couldn’t get pictures of the calf, which was protected in the middle of the herd and hidden by thick bushes. One elephant spotted one of us, and the herd quickly fled. We lost our chance.

We then headed back to check on the Ugab herd, more accustomed to humans and vehicles, near Anigab and the Ugab River.

We found it in the riverbed.

We hadn’t spotted them before entering the riverbed, but we passed by a cow and soon saw one of the dominant bulls, Big Ben or Bennie, in our way. There was no escape route. He passed by our car. We sat in silence, holding our breath, and could appreciate his majestic stature. I instantly fell in love with him. I couldn’t take my eyes off him, and I was at the right place at the right time.

After he passed by, we had the chance to get out of the car and climb a koppie to see the entire herd pass by. It was breathtaking—a moment I will remember for a long time, if not always.

Clearly, this herd was used to cars and passed by peacefully next to us. Each time there is an elephant or wildlife sighting, EHRA staff records the information for research to better understand their habits.

We followed them and anticipated their next move. They went near the Brandberg White Lady Lodge, where we were waiting for them. Meanwhile, our guide reminded some guides of the code of conduct as they were too close to the elephants. EHRA has legitimacy in the area, and this was done diplomatically, from what I could observe.

Back to the elephants, they tried to drink from a chalet’s private swimming pool. They didn’t like the taste of the water and used it only to cool themselves and enjoy a sand/mud bath. Next, we found them near another chalet, where they broke a water pipe and enjoyed clean, fresh water. Apparently, this is a habit, as we were told by the lodge.

The next day, we were supposed to continue observing them, but plans changed during the night. We had to go back to the Frenzy herd. The local guide saw the calf limping, and we needed to get a closer look, take as many pictures as possible to document the injury, and confirm if a vet team was needed via helicopter. It took us 2 hours of driving back east.

When we arrived after lunch, we tried to find the herd based on the office’s general indications. We drove through the thick bush, avoiding thorny branches, which was challenging for everyone and the equipment. Despite circling around, we couldn’t get close enough or spot them clearly. We had to return to the main road and call it a day. We slept next to the water point again, hoping the elephants would come at night to drink, giving us a chance to track them the next day before heading back to base camp.

We were lucky. They came during the night. We observed some of them, possibly a lonely bull or another herd, and later the Frenzy herd returned. The next day, they were still near the road, and we quickly spotted them after passing a broken-down car with 20 people being driven back to their village 50 km away. They were fortunate as the elephants were very close, and they hadn’t realized the danger of sleeping in those bushes—approximately 7 adults and the rest children.

We continued on foot and split into two teams. I was part of the small delegation responsible for getting a good shot of the calf. I was thrilled and scared at the same time. We moved quietly for an hour, bending and making as little noise as possible. Our guides quickly spotted the elephants and anticipated their moves, while I struggled. We almost got surrounded by the herd. The matriarch sensed something, stopped her activity, and looked around, trying to identify us. We were not standing and hiding behind the bush. It was tense. We were prepared to run if needed. The calf remained hidden among the cows. One volunteer managed a shot, but it was too blurry and not precise enough to use.

I was highly impressed by the moment, not reassured at all, clearly scared, but I followed the guides’ instructions, trusting them. I hope to improve and return someday. This requires time and practice. My eyes are not yet trained for this task, and my vision is getting poorer with age. Sometimes I doubt my ability to become a field guide in the near future. I’ll see—no need to worry now, but I’m conscious of my physical limitations.

In the meantime, the rest of the team was worried. They had no news from us and couldn’t see us, even from atop the car with binoculars. Unfortunately, we had to abandon the mission and headed back to the Ugab River.

On our way back, we witnessed another HEC incident. A bull had bypassed one of the three electric fences set up by EHRA and harvested the garden of a vegetarian lady who relies solely on her crops for food. It was impressive to see the intelligence of this animal and how he bypassed a 9000-volt electric fence. I’m very interested in how EHRA will address this. The project is experimental, with only three fences installed so far. EHRA will also provide seeds for the lady.

We then enjoyed another sighting of this famous herd. Big Ben was there again, majestic as ever. These elephants clearly inspire respect.

This marked the end of patrol week. It went by so quickly.

Patrol week was really challenging, contrary to my expectations. As we were told, EHRA is not a safari company. We comply with goals greater than ourselves and our requirements as volunteers, on behalf of the elephants.

I also noticed that the guiding team was concerned about the volunteers’ experience with elephant sightings, as for some of us, it was our first time. Everything was taken into account, balancing greater goals and the volunteering experience delicately.

Patrol week is also a very intense educational moment for the local population and the volunteers. I’m really grateful for the availability and knowledge of our guides. I have seen and learned a lot—scientific and common names of trees, local surroundings, and the behaviors of desert-dwelling elephants. Our guides were equipped with reference books that we could consult anytime.

I also wanted to share that one of our guides is an intern at EHRA. She was one of the reasons I chose this organization, thanks to our nice chat and what she shared about her volunteering experience. In the meantime, she completed a 2-month FGASA training with EcoTraining in South Africa. She brought all the training reference books and let me consult them, sharing her training experience. I got plenty of tips and ways to approach it now. Really convenient. I could start preparing in advance, which I like.

Another nice coincidence and gift from life, if you ask me.

All in all, I couldn’t be happier and feel like I’m on the right track. It’s soothing to myself while staring at the vast desert landscapes, which I loved. I shared this with one of the staff members. To my surprise, he said that these desert landscapes are a sign of sadness for him. They used to be greener with a lot of wildlife. Lions used to live in the area but have starved to death, posing a threat to the local population.

Climate change has had a great impact in just a decade, as shown by the materials from EHRA’s educational center.

Food for thought, as always.

Leave a reply to Zebra2x22 Cancel reply