Part of the trail guide training (the ability to guide guests on foot in the savanna) involves advanced rifle handling.

I hadn’t fully understood what that entailed. Before this training, I had never used a firearm in my life, and I’m grateful to live in Europe, where firearm licenses are restricted.

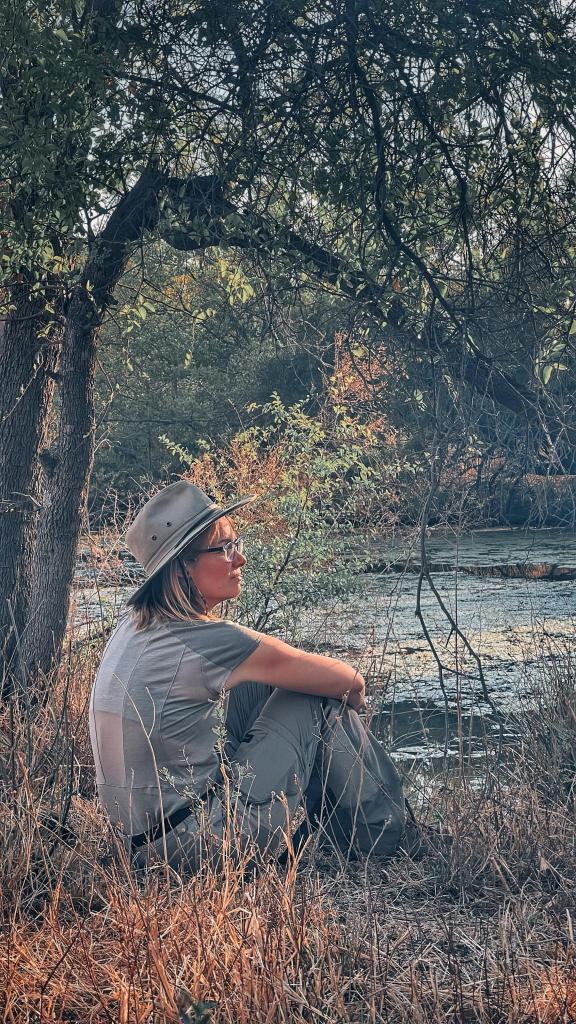

The first two weeks of training focused on walking in the savanna and approaching dangerous game. Those weeks were incredible—we had 28 encounters in total: lions, elephants, leopards, rhinos, and buffalo, all on foot. It was truly exhilarating. We learned how to approach as close as 30 meters, sometimes even closer, ideally without being seen or heard. We were taught how to track animals and how to react in case of a close encounter.

Every factor is considered: terrain, concealment, escape routes, sunlight, wind, soil, animals, shifting conditions, and guests. The goal is to stay within the animal’s comfort zone, where it tolerates our presence and continues its activities—this is known as an ethical encounter.

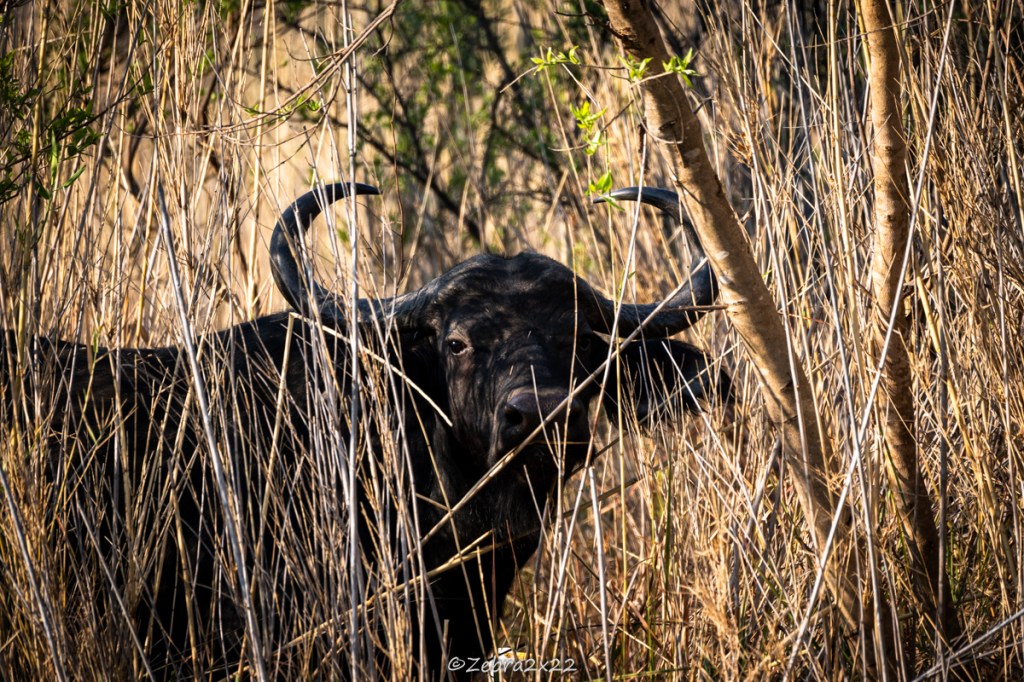

When you get close and are spotted, you feel incredibly small against such raw power. Some buffalo bulls showed warning signs, prompting us to retreat, as did a few elephant bulls. A lion once saw us, tolerated our presence, and went on with his activities. Most of the time, animals will avoid human encounters if they detect us. The best sightings are when animals, like rhinos, are completely unaware of our presence—seeing them sleeping, feeding, or playing up close is a blessing.

Walking in the savanna is a completely different experience from game drives. You’re immersed in nature, with minimal interference from human activities. You’re not just a witness; you’re a part of nature with all that it entails.

Photos by A. Scaramuzza (Fastsky)

To be authorized to guide on foot in a reserve, you need to be proficient in handling a high-caliber rifle capable of stopping a dangerous animal charge. Part of the training involves familiarization with ballistics, calibers, the working components of a manually operated rifle, the legal framework in South Africa, and firearm cleaning and maintenance. There’s a written test under the FGASA framework, covering all aspects of being a trail guide: knowledge of dangerous animals, procedures for charges, recognizing animal warning signs, planning primitive trails, important considerations for guest interactions and animal approach, trail briefing, and required gear.

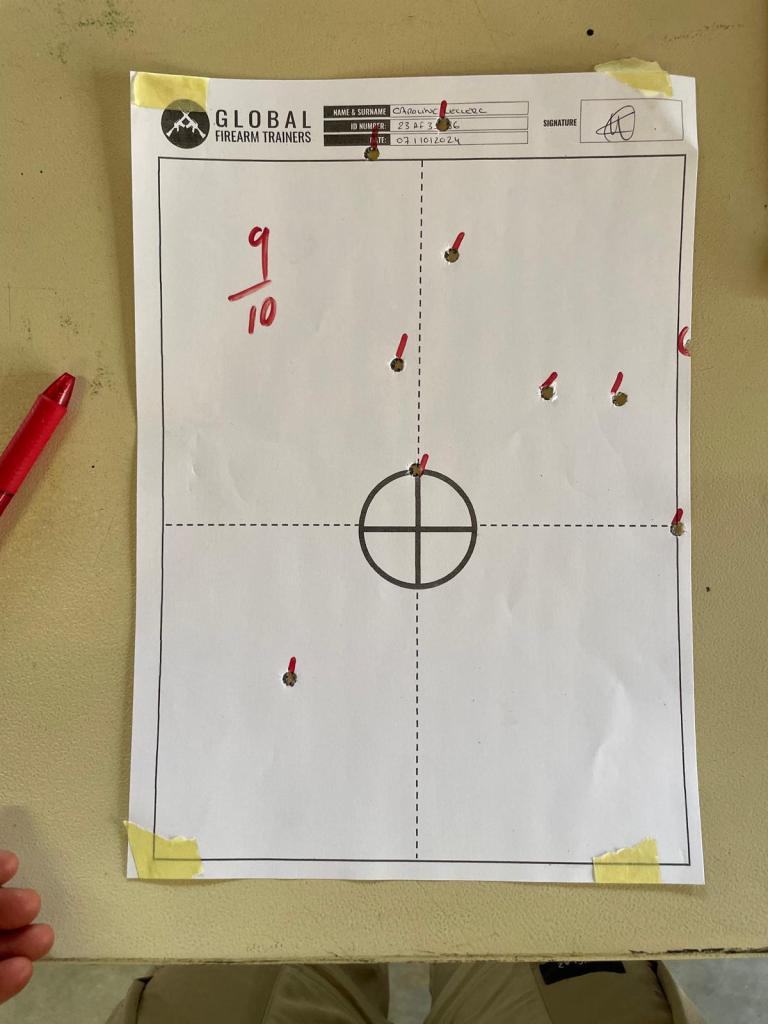

There’s also a written exam under South Africa’s legal framework (the Professional Firearm Trainers Council, or PFTC) and practical tests on rifle accuracy. The test requires hitting an A4-sized target 8 times out of 10 with different calibers (up to .457 and using reticles) from 30 meters, both standing and kneeling.

During our two weeks of practice as observers, we had one hour of rifle handling practice daily. We started by manipulating the rifles with and without dummy cartridges to prepare for the following tests:

- Loading three cartridges, chambering, and aiming within 15 seconds, blindfolded.

- Hitting a target three times, reloading a full magazine, handling a misfire, and canting the rifle—all in under 26 seconds.

At first, I had to get used to handling a rifle without cartridges, a completely new experience for me since I had never touched a rifle before. Introducing dummy rounds added another layer of challenge—it felt even more real. Eventually, I got used to it and started performing well in the exercises we practiced every day.

Then came two days of practice with live rounds and higher calibers. We began with the previous exercises and added new ones:

- No time limit; target placed 12 meters away; all 5 shots needed to hit the target.

- In under 20 seconds, aim at targets at 12m, 8m, and 4m; reload, chamber, and aim again in under 20 seconds.

- Simultaneous shots at targets at 8m and 4m, with an image of a buffalo.

We increased the caliber progressively from a .308 to a .375. I had to overcome the pain from the .375’s recoil—it was intense. Eventually, I switched to a .458, which, despite the higher caliber, was less painful for me. Adjusting my stance also helped me shoulder the rifle better and protect my shoulder.

The pain had an unexpected effect: my body began anticipating each shot. Any slight movement—like closing my eyes or adjusting position—would affect accuracy. I had been much more precise before experiencing recoil. I took anti-inflammatories for the pain, but the anticipation remained, causing many shots to veer left due to small, barely perceptible movements, like blinking.

At one point, I really questioned whether this was the right path for me. Did I truly need to go through all this to walk in the savanna and guide guests? Was the price worth paying: enduring physical pain, taking medication, handling lethal tools, and managing heavy rifles?

The instructor took the time to work with me and the entire group, which I appreciated deeply. Sometimes, he would load the rifle without me knowing if it contained a dummy or live round. When he sensed I was ready and steady, he would load a live round. I improved, but I wasn’t there yet. I only passed one of the five exercises during practice. This particular exercise was the hardest for me: instead of a standard round target, we used images of buffalo, aiming specifically at the brain. For someone who has been a vegetarian for ethical reasons for over ten years, shooting at a buffalo image was yet another challenge.

This training was extremely demanding, and I had to find inner strength to get through it. I discovered that closing my non-dominant eye improved my precision and helped keep my dominant eye focused.

But I wasn’t done yet.

Then came the exam days. We had to repeat the exercises we’d been practicing. The most difficult one for me was hitting five shots at 12m in my own time. I kept telling myself that I could do it, trying to stay positive. I used all my attempts and was marked “not yet competent,” meaning I’d only have two attempts per exercise, instead of four, in future tries—adding extra pressure on the remaining exercises.

Overcoming the ‘not yet competent’ status was a real challenge—it was my first experience of failing something. I had never failed anything before and was putting a lot of pressure on myself. As the last one to attempt the exercises, I saw each hurdle and success of the other students, which probably only heightened the pressure and made it harder to calm my mind.

After I was marked ‘not yet competent’ on the first day, I went somewhere private and cried. I felt frustrated and realized I wasn’t as prepared as I had thought.

The next day, I managed to succeed in the exercise. I approached each attempt as practice, releasing the pressure and feeling grateful for the opportunity to continue. The remaining exercises were timed, which allowed less room for overthinking—requiring me to focus on accuracy and speed, which I did successfully.

The last exercise, the most difficult, was the simulated animal charge. This test incorporates all the skills we learned. It’s incredibly intense: an image of a charging buffalo approaches at about 40 km/h, starting 30 meters away. When you see the charge, you begin by shouting to deter it while continuously giving instructions to your guests. If the animal doesn’t stop, you chamber and aim when it reaches 20 meters, but you’re not authorized to shoot until it’s within 10 meters, as some animals stop their charge 10-15 meters away. You need to give them that benefit of the doubt.

Once you’ve hit the brain, you must fire again at the brain, load the rifle while remaining aware of other potential dangers, perform a coup de grâce and corneal reflex check, reload, secure the rifle, and manage the guests. You only pass if you hit the brain and follow all procedures correctly; any shot outside the brain counts as a failure. We only had one live round for the initial shot, with the rest being dummies.

Here is the instructor’s demonstration video to give you an idea.

After the test, I had a plane to catch due to a visa limitation that prevented me from staying over three months, so my program had to be rearranged. I was able to change the lineup and go second this time.

We had the chance to practice with both dummy and live rounds, doing two attempts each. My two practices with live rounds weren’t successful; I aimed correctly but just below the brain. I decided to go for the official attempt, given our limited cartridges, and I succeeded on my first try.

Here is the result of my shot.

During the procedure, I felt an unexpected surge of satisfaction—I saw the shot land and shouted, ‘The animal is dead,’ feeling a real sense of accomplishment. I never imagined I would say that and mean it. When I started this training, my goal was to avoid ever using the rifle, to avoid creating circumstances where I’d need it, but to be prepared if things went wrong.

The exercise was not easy; it took several attempts for many students, and unfortunately, not all succeeded.

Now, I am well on my way to becoming an apprentice trail guide. I still need to complete one last practical assessment after completing 10 hours of mentorship upon returning to South Africa.

I am very proud of what I’ve achieved, of the process, and of overcoming all the challenges involved in handling a rifle. Now, I look forward to some well-earned vacation—wish me a great and restful break!

Please find some photos of the wildlife I encountered during those training weeks.

Leave a reply to Olivier Massé Cancel reply