During the month of March, I had the chance to visit Zimbabwe for some more lodges exploration.

The schedule was busy—on average, we stayed just one night in each place before moving on to the next. It was intense compared to regular safari vacations, where it’s strongly recommended to stay at least two or three nights in one spot to really get to know the area, settle in, and get the most out of the experience.

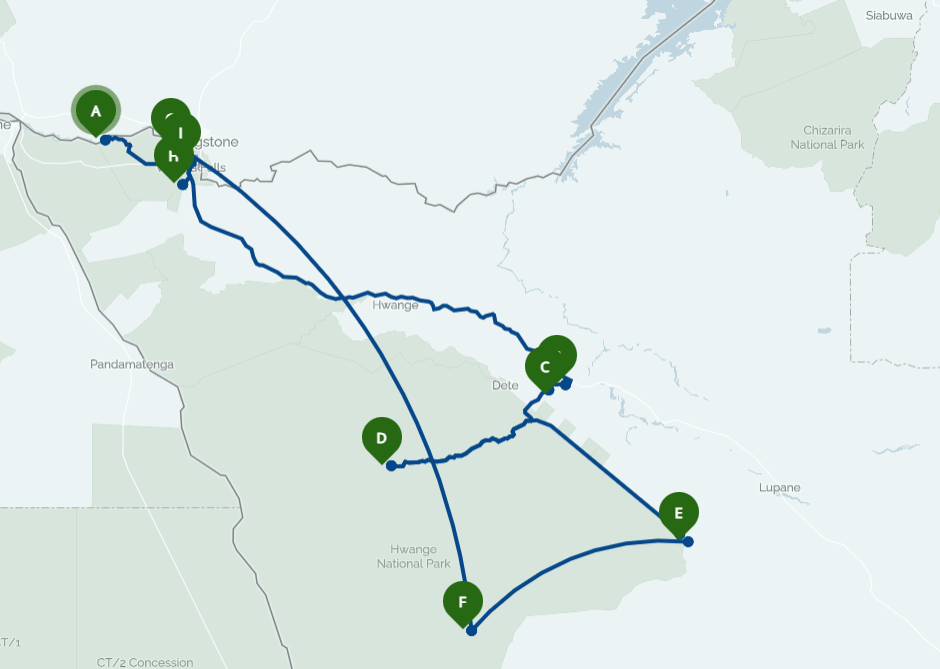

Here was our program: arrival in Victoria Falls, Eastern and Southern Hwange National Park, and back to Victoria Falls.

As usual, I arrived with no expectations. I knew the trip would end with a visit to Victoria Falls which was a dream come true, I’d hoped one day I’d see the Falls for myself.

The trip had three main parts:

- Exploring the Zambezi River and National Park, ending at Victoria Falls

- Visiting a private concession on forestry land near Hwange National Park (Amalinda Collection Lodges)

- Discovering Hwange National Park with Imvelo Safari Lodges

Zambezi River and Zambezi National Park for a start

We started along the Zambezi River with a peaceful and quiet pace: a sunset cruise on the river and a few game drives in Zambezi National Park.

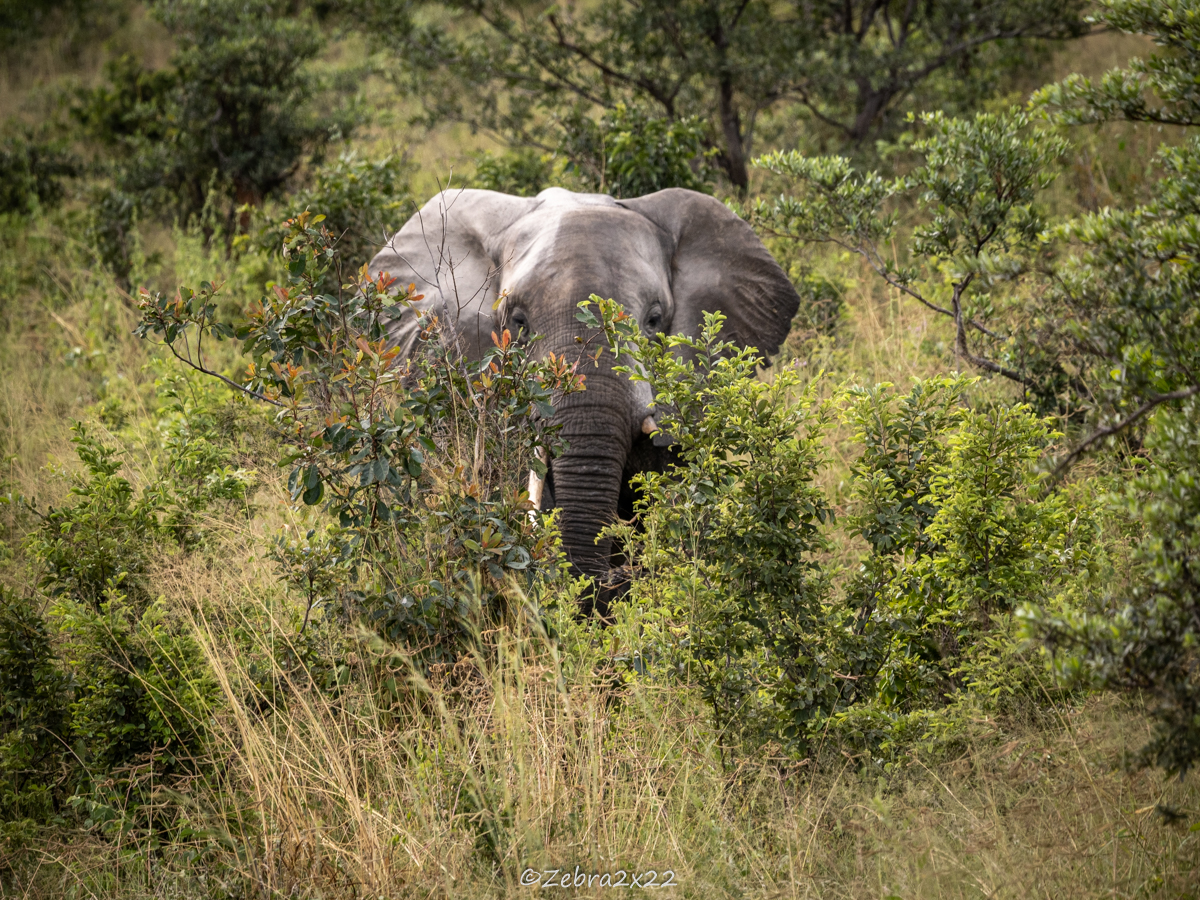

Wildlife was hard to spot due to the lush, abundant vegetation—animals were scattered and well-camouflaged.

Still, I managed to capture some photos of a “white elephant.” Its pale color was due to the light soil in the area. Elephants love to cover themselves in soil after a bath—it helps protect them from the sun and keeps parasites away, especially when they rub against trees.

I hadn’t known the expression “white elephant” meant something expensive and useless, which clearly is not the case here.

We also spotted zebras.

Amongst other animals.

So I got to see two of my favorite animals right from the beginning.

We came across lion and leopard tracks but, unfortunately, couldn’t find the animals themselves.

Community and Conservation Matter

What struck me just as much as the wildlife was the focus on community engagement and conservation. These aspects are increasingly important when choosing or recommending safaris—thoughtful choices can have a far greater impact on local people and ecosystems.

During our stay in Victoria Falls, we visited the Victoria Falls Wildlife Trust and its surrounding facilities. I was surprised by how many tourists were eager to learn more and joined the tour. The trust runs several impactful projects, including:

- Rescuing animals affected by poaching or accidents, with the goal of rehabilitating and releasing them (using both soft and hard release techniques); two vets are based on-site.

- Community guardianship programs, where locals are trained to protect their gardens and livestock from wildlife. Lions are deterred with vuvuzelas, and for elephants, chili peppers are fired from potato guns! The trust also uses GPS collars to track animal movement and creates mobile BOMAs—movable enclosures that can hold up to 600 cows and are relocated weekly to prevent conflict with predators.

- Wildlife Forensics Laboratory: The only lab of its kind in the KAZA Transfrontier Conservation Area, it performs species identification tests on meat confiscated from poachers, analyzes dead animals for toxicology and serology, and even determines the origin of seized ivory.

- Community Education and Training: Local communities are educated about key species such as elephants and vultures, raising awareness and fostering a culture of coexistence and conservation.

Elephant Interaction at Elephant Camp

We also took part in one of the guest experiences offered at Elephant Camp: what they call an “elephant interaction.” The format varies depending on the number of tourists. For larger groups, like ours, the interaction takes place at a designated center. The elephants—tame individuals that were orphaned due to poaching or kept as pets—come up to a balcony where guests can briefly touch them. This is followed by a feeding session using pellets, though without direct contact.

The elephants are in good health and appear well-treated. They roam freely in the park, though each is accompanied by a shepherd carrying a stick. These elephants cannot be released back into the wild, so the interaction experience helps fund their care.

The tourists were absolutely thrilled. The experience is well-run and polished, complete with a presentation introducing each elephant (though I regret not taking notes), a souvenir shop, professional photographers, and cameramen producing high-quality paid videos.

I hated it.

I understand the rationale: raising funds to support the elephants’ care and creating lasting impressions that may lead to donations or advocacy. But I couldn’t help wondering—isn’t there another way? Another way to raise awareness and money, without staging animals for mass human interaction?

Ethical or not (and some sources online label this program as ethical), it felt to me like a well-rehearsed performance designed for revenue collection. The interaction takes place three times a day, and smaller groups are even taken to meet the elephants on foot in a more natural setting. Everyone around me was genuinely happy with the experience. But for me, it was a commercial moment in contrast with the wild encounters I’d had elsewhere.

Victoria Falls

We had two memorable activities during our stay in Victoria Falls:

- A river cruise with a knowledgeable guide focused on birds

- A walking safari in the park with another experienced guide

Both were exceptional. I always enjoy being on a boat, and this cruise was no exception. The guide had deep knowledge of local birdlife, which made the experience even richer. Since my nature guide training, I’ve discovered a real passion for bird identification—and this trip became another opportunity to observe and photograph them. I’ve now increased my Southern Africa life list to over 200 species.

Here is an overview:

The walking safari was another highlight. We began in a 4×4 to get closer to fresh tracks and increase our chances of encountering dangerous game. Luck was on our side—we spotted a lion at sunrise!

We tracked elephant bulls on foot, taking frequent stops to observe insects and plants along the way. In the distance, we saw two buffalo bulls, but we couldn’t maintain visual contact and failed to relocate them after they moved off.

So, we switched to trailing elephants instead. We’d glimpsed one earlier while walking but had prioritized the buffalo. Later, we encountered an elephant bull dust-bathing—he passed very close to us. It was one of those intense, grounding moments that only a walk in the wild can bring.

Photos H. Gumpo

After trailing a herd that had crossed the Zambezi River, we spotted them in the distance—but it was time to head back to our vehicle.

On the way, we crossed paths again with the same elephant bull from earlier that morning. He approached our vehicle while we were still about 50 meters away. We paused, watching quietly.

He sensed our presence. Slowly, deliberately, he walked toward us. We stood perfectly still. No one said a word. Four times, the bull advanced—head high, ears fully extended, trampling the sand and tossing sticks. He got within 5 to 10 meters of us.

The guide remained calm and silent, only lifting his rifle ever so slightly when the bull came too close. That subtle movement was enough—the elephant paused, let out a sharp trumpet, and eventually turned away.

Later, we discussed the encounter with our guide. He explained that the bull couldn’t quite identify us as humans because we hadn’t spoken. Our stillness confused him. If we had talked earlier, he likely would have left sooner.

Photos H. Gumpo

It was a truly powerful experience. Based on my own training, I would have spoken to the elephant—gently, to announce our presence. It’s fascinating to see how different guides handle these intense encounters.

Soon after, we stumbled upon a herd of elephants with calves, bathing and rubbing against one another in the river. We watched them from outside the vehicle, surrounded by the sights and sounds of the river, as if we were part of the herd ourselves. Another incredible moment.

What a way to start the day—memories I’ll never forget, right before heading off to Victoria Falls.

The Legendary Falls

No trip to this region is complete without visiting Victoria Falls, one of the most iconic natural wonders in Africa—and the world.

The falls sit on the Zambezi River, Africa’s fourth-longest river after the Nile, Congo, and Niger. They’re shared between four countries—Namibia, Zambia, Zimbabwe, and Botswana—and appear on the bucket list of travelers from all over.

Victoria Falls ranks as one of the top three waterfalls in the world according to the World Waterfall Database, alongside Niagara and Iguaçu Falls. Each is measured by a combination of height, width, and water volume. While Iguaçu has more individual falls, and Niagara more fame, Victoria Falls boasts the largest continuous curtain of falling water on Earth.

Key Facts:

- Width: 1.7 km (10th largest globally)

- Height: 107 meters (around 800th)

- Volume: 1,100 m³/second (13th)

- Peak Flow: In April/May, over 550 million liters per minute pour over the edge

The result? A constant mist cloud that rises above the gorge—“The Smoke That Thunders”—which nourishes the surrounding rainforest and its astonishing biodiversity. Over 500 bird species have been recorded in the area throughout the year.

When you visit the falls, bring a raincoat—or rent one nearby for $3. You’ll likely need it.

What struck me most was the sound—a powerful, continuous roar that fills the air and dominates the landscape.

The rainforest around the falls is lush and dense, full of vibrant life. You can’t see the entire waterfall on foot—only glimpses from various viewpoints. To see it in full, you’d need to take a helicopter flight. There’s even a famous sunrise spot where you can catch a rainbow arching over the gorge.

I admit, the falls were impressive.

During our time in Victoria Falls, we traveled with a recommanded local guide—someone deeply experienced in the bush. I loved our conversations. For him, walking safaris are more than just a wildlife experience.

They’re transformative.

He believes that when you come face to face with dangerous game, it humbles you. In that moment, it doesn’t matter who you are—a billionaire or a farmer—nature is not making any difference. You may need to rely on someone else. You may face your deepest, primal fears.

He is convinced animals can see through you—they strip away your layers and confront you with your true self.

That deeply resonated with me.

I’ve had a few close encounters with dangerous animals. I was scared that I wouldn’t be able to hold my ground—that my reptilian brain would kick in and make me run, straight into danger. I dreaded my first lion encounter, especially the sound of a growl.

And yet… when it happened, when a lioness growled just meters away, I didn’t move. I didn’t panic.

I was proud of myself. I remained calm.

Did walking safaris change me? Maybe. I believe the real change began even before I stepped onto the trail. It started when I made the decision to change my life and follow this path.

Conservation in Eastern Hwange National Park

We made our way to Amalinda Safari Collection. The camps were stunning—thoughtfully designed, comfortable, and harmoniously integrated with their surroundings.

As we moved toward Hwange National Park, I learned about the story of Cecil the lion—an iconic male who lived in the park and was shot by an American dentist in 2015. Cecil was 13 years old and collared for research. His death moved the international community, and shed light on the darker side of trophy hunting.

The wildlife is amazing.

But beyond the wildlife and the scenery, what truly inspired me were the community projects they support through conservation tourism.

Amalinda works in partnership with an organization called Mother Africa Trust (Building Zimbabwe One Person at a Time), and together they channel part of the conservation levy into projects that uplift local communities while supporting wildlife conservation.

Here are some of the initiatives I had the chance to explore and learn about:

The Mushroom Project

A brilliant, low-effort, high-impact income-generating project.

- 18 women have been trained and given facilities to grow mushrooms.

- Each cycle produces about 30 kg every two months, sold at $5 per kilo.

- Each facility contains 6 rooms representing 6 production cycles.

- The work involves sterilizing the rooms, preparing substrate from dead leaves, and filling grow bags with 3 layers of substrate and 2 of spawn—a process that takes just a few hours.

- After harvesting, the follow-up is minimal, and each woman earns an income from this activity which can contribute to school fees : $30 per child per trimester.

- Their main challenge? Accessing affordable spawn to keep the project going.

Income-Generating Skills

Local people are trained in a variety of sustainable practices:

- Beekeeping

- Basket weaving

- Fishing

- Farming for self-sufficiency

These provide families with new income streams and improve food security.

Egg Production

Another project aims to boost local nutrition and income through egg farming.

Preventing Human-Wildlife Conflict

A major concern in conservation areas is the safety of livestock. Amalinda and Mother Africa have tackled this with BOMA enclosures—protective kraals that keep cattle safe at night.

- 32 permanent BOMA and 2 mobile BOMA have been built.

- Mobile BOMA are especially innovative: they’re cost-effective, movable, and their use fertilizes the land, improving soil health and reducing tick infestations.

These structures protect livestock from predators, support sustainable agriculture, and reduce conflict between wildlife and rural farmers.

Wildlife Conservation

On the wildlife front, funding also goes toward active conservation measures:

- Animal collaring (approx. $5,000 per collar) to monitor movement and behavior

- Snare removal to protect animals from illegal trapping

- Camera trap setups for research and surveillance

- Anti-poaching patrols within the concession

Community Development

Amalinda and Mother Africa are also contributing to a range of services:

Health

- Construction of waiting rooms for pregnant women at local clinics

- Refurbishing nurse accommodations to improve staff retention and care quality

Education

- Providing scholarships

- Building classrooms and teacher cottages

- Supplying furniture and bicycles for students who live far from school

- Offering free meals to improve attendance and learning performance

Volunteer Program

To support and scale these efforts, they offer volunteering opportunities. Visitors can directly participate in projects, offering time, skills, and support that go far beyond a financial contribution.

My Favorite Program with Imvelo Safari Lodges

Last but certainly not least, I want to share my favorite experience from this trip: discovering the work of Imvelo Safari Lodges.

From the moment we arrived, we were hosted by the managing director himself, who accompanied and drove us throughout our stay. Imagine a well-connected local, a former ranger, a former provincial wildlife officer, responsible of wildlife in the Zimbabwe Forestry Commission, passionate and grounded, deeply committed to wildlife conservation—particularly for rhinos and elephants.

What stood out most? His belief that the key to wildlife preservation lies in the community.

His philosophy is clear: when conservation benefits everyone, people become part of the solution. We spent hours in the front seat of his game viewer, immersed in powerful conversations—his vision, his challenges, his relentless drive. Every now and then, we’d pause to step out and observe elephants nearby.

He struck me as passionate, visionary, direct, and respectful—exactly the kind of person who inspires me.

Community Rhino Conservation Initiative (CRICI)

One of Imvelo’s proudest achievements is the reintroduction of rhinos into the communal areas next to Hwange National Park, a project that took decade in the making.

- This required a sacrifice from local communities, who started to give up 220 hectares of grazing land to create a safe haven for rhinos.

- In 2020, the land was fenced, and two white rhino bulls were introduced in 2022, with the goal of minimizing human-wildlife conflict.

- Each visitor pays a conservation fee, which goes directly back to the communities—who decide how to use the funds independently. One of their first decisions? To fund a new clinic.

The rhinos are monitored 24/7 by the COBRAS, a dedicated team of trained rangers, many of whom are former poachers turned protectors.

- A canine unit has also been introduced, adding another layer of security.

- COBRAS patrol daily with the rhinos, collecting data on their movements, behavior, and preferences.

Today, there are two fenced areas totaling 10.5 km² and four rhinos living under this pioneering model.

Hwange Community Rhino Program

Imvelo’s Broader Impact

Imvelo Safari Lodges’ impact goes far beyond rhino conservation. Funded by donors and their lodges, they support community development, health, education, and water access across the region.

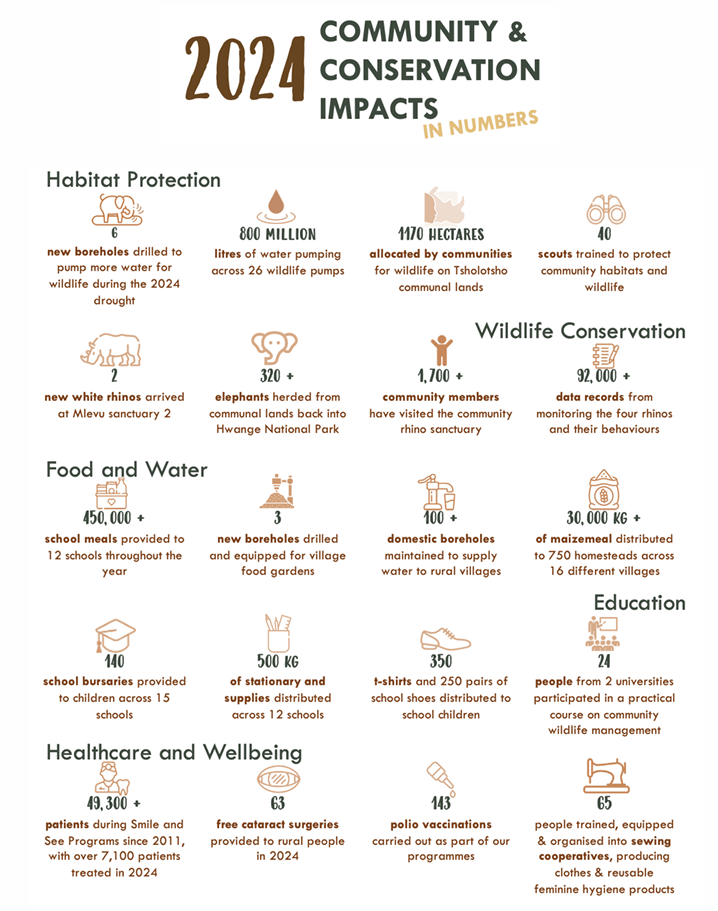

Here are just a few of their 2024achievements that blew my mind:

- Maintaining 26 solar-powered pumps in Hwange National Park to provide water for elephants and other species, pumping up to 800 million liters a year.

- Providing over 3.5 million school meals in the past decade—that’s more than 450,000 lunches every year.

- Running the Smile and See program, delivering free eye and dental care to nearly 50,000 patients, often transforming lives with critical treatments.

- Offering education support, including bursaries, wildlife awareness, and school supplies.

- Maintaining over 100 domestic boreholes, bringing clean water directly to communities.

All of this was very impressive :

- Watching the COBRAS patrol the sanctuary, observing the Malinois dogs in training

- Listening to life-changing medical stories from the Smile and See program

- Staying at Jozibanini Camp—one of the most remote, raw, and remarkable places I’ve ever visited (and where I even convinced family to join me!)

- Meeting the core team behind Imvelo’s efforts

It was inspiring. A program that manages to tie together ecology, humanity, and local empowerment.

Before leaving, I shared my appreciation for what I had seen—and my desire to come back and contribute. The response?

“Don’t be a stranger.”

That phrase resonated. It felt like an open door, an invitation. And maybe, just maybe, one day I’ll walk through it again—perhaps through their volunteering program.

I came expecting landscapes and wildlife, and I left touched by the depth of community engagement behind the scenes.

Tourism, when done with purpose, can be a real force for change.

The wildlife and the ecosystem are amazing, as you can imagine.

P.S.: If you’d like to dive deeper into the Hwange Community Rhino Program, you’ll find plenty of perspectives online. A number of travel blogs and articles document personal experiences and reflections about the project. Here is one.

What’s Next?

For now, I’m focused on my upcoming two-month volunteering program in South Africa, where I previously completed my internship in late 2024. But something tells me this isn’t the end of my story with Hwange and Imvelo—it might just be the beginning.

Leave a reply to Zebra2x22 Cancel reply